Commissions & Premières

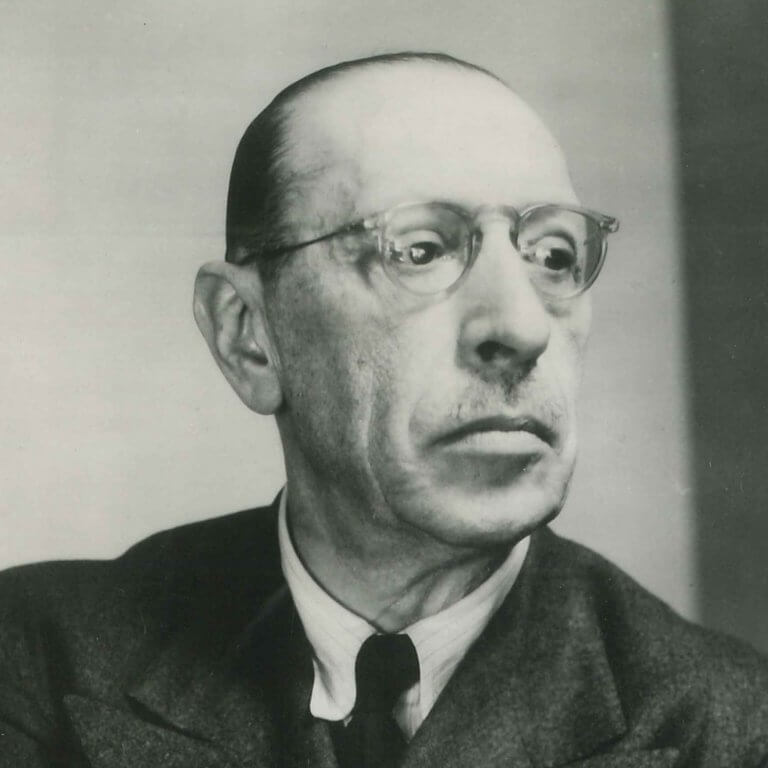

Igor Feodorovich Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), a Baltic resort near St Petersburg, on 5 June (17 June, New Style) 1882, the third son of Feodor Stravinsky, one of the principal basses at the Maryinsky (later Kirov) Theatre in St Petersburg. Stravinsky’s musical education began with piano lessons at home when he was ten; he later studied law at St Petersburg University and music theory with Fyodor Akimenko and Vassily Kalafati. His most important teacher, though, was Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, with whom he studied informally from the age of twenty, taking regular lessons from 1905 until 1908.

Although Stravinsky’s first substantial composition was a Symphony in E flat, written in 1906 under the tutelage of Rimsky-Korsakov, it was The Firebird, a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev and premiered by his Ballets Russes in Paris in 1910, that brought Stravinsky into sudden international prominence. In the next year he consolidated his reputation with Petrushka, like The Firebird a transformation of something essentially Russian into a work of surprising modernity. Stravinsky’s next major score – a third ballet commission from Diaghilev – is one of the major landmarks in the history of music: the blend of melodic primitivism and rhythmic complexity in The Rite of Spring marked the coming of modernism in music and was met with a mixture of astonishment and hostility. Stravinsky, now a Swiss resident, became established, as the most radical composer of the age.

A rapid succession of works – The Nightingale, an opera, in 1914, Renard in 1915, The Soldier’s Tale in 1918, the Symphonies of Wind Instruments two years after that – all reinforced his aesthetic dominance. The explicitly Russian flavour of his music – played out in the Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920), the opera buffa Mavra (1922) and Les Noces (1923), for four solo voices, chorus and an orchestra consisting of four pianos and percussion – now gave way to a more refined neo-classicism, beginning with the ballet Pulcinella (1920), for which Stravinsky went back to the music of Pergolesi, reworking it into something completely personal.

1920 was also the year that Stravinsky settled in France, taking French citizenship in 1934. Stravinsky expected to be elected to a vacant seat in the Académie française following Dukas’ death in 1935, and felt rebuffed when Florent Schmitt was elected in his stead. His ties to his adopted homeland were further loosened when, in a mere eight months, from November 1938, Stravinsky suffered the deaths of his daughter Lyudmilla, aged only 29, his mother and then his wife (and cousin) Catherine (née Nossenko); faced with an imminent war in Europe, Stravinsky and his second-wife-to-be Vera Sudeikin (née de Bosset) emigrated to the United States. After a year spent on the East Coast, including a stint as a lecturer at Harvard University, he and Vera soon settled in California, which they were to make their home for the rest of their lives.

Pulcinella turned out to be only the first of many works in which, over the next two decades, Stravinsky subdued the music of the past to his own purposes, among them the ‘divertimento’ The Fairy’s Kiss, derived from Tchaikovsky, and the ballet Apollon Musagète, both premiered in 1928. Two choral-orchestral works – the oratorio Oedipus Rex (1927) and the Symphony of Psalms (1930) – showed that he could also work on an epic scale; and it was not long before he tackled a purely orchestral Symphony in C (1938), which was followed within four years by the Symphony in Three Movements. With Perséphone (1934), Jeu de Cartes (1936) and Orpheus (1946), the series of ballets also continued, generally in collaboration with George Balanchine, a partnership as important to dance in the twentieth century as Tchaikovsky’s and Petipa’s had been in the nineteenth. Stravinsky’s neo-classical period culminated in 1951 in his three-act opera The Rake’s Progress, to a libretto by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman.

One of the most unexpected stylistic volte-faces in modern music came in 1957, with the appearance of the ballet Agon; Stravinsky himself conducted its premiere at a 75th-birthday concert. Hitherto he had ignored Schoenbergian serialism, but in 1952 he began to study Webern’s music intensely and Agon was the first work in which he embraced serialism wholeheartedly, though the music that resulted was entirely his own – indeed, it has a formal elegance that he seemed to have been trying to capture in his neo-classical period. The chief works from Stravinsky’s late serial flowering are Threni, for six solo voices, chorus and orchestra (1958), The Flood, a ‘musical play for soloists, chorus and orchestra’ (1962), the ‘sacred ballad’ Abraham and Isaac (1963), Variations for Orchestra (1964) and Requiem Canticles (1966).

Stravinsky was also active as a performer of his own music, initially as a pianist but increasingly as a conductor. The first among contemporary composers to do so, he left a near-complete legacy of recordings of his own music, released then on CBS and now to be found on Sony Classical. His conducting career continued until 1967, when advancing age and illness forced him to retire from the concert platform. His tenuous grasp on life finally broke on 6 April 1971, in New York, and his body was flown to Venice for burial on the island of San Michele, near to the grave of Diaghilev.

Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes

Funeral Song, Op 5

for Orchestra